Waltz à Deux Temps (d'Orsay, 1843):

The German waltz, à deux temps, is exactly contrary in its principle to the Rhenish waltz. The motion, instead of being always backward or forward, is always directly sideways. The beats of the feet, instead of being in three time, are in two time. The step, or these beats of the feet, may be said to begin with the contrary foot to that on which they begin in the Rhenish waltz, and the turn is at a different time in the music.

I shall give two modes of doing the German step. There are many.

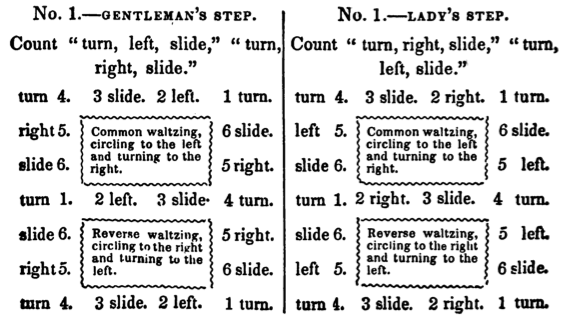

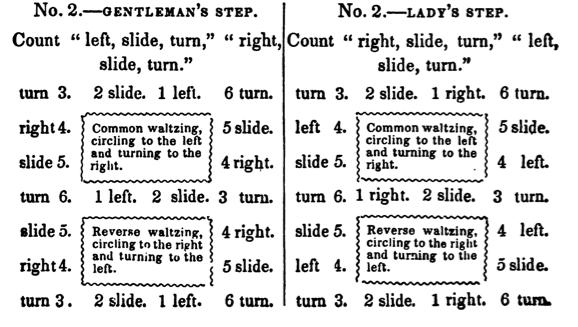

No. 1.—Gentleman's Step In The Figure Of 8, A Deux Temps

Count "turn, left, slide," "turn, right, slide." On the word "turn," turn to the right on the right foot, making a beat with it; that is, while standing on the right foot, make a slight rise, and again fall on it. At the same time, move the left foot to the left, and bring it to the ground. On the word "left," pass the weight over the left foot without any beat. On the word "slide," make a slide to the left, with both feet as much as possible at once. On the word "turn," turn to the right on the left foot, making a rise and a beat with it, at the same time moving the right foot to the right, and bringing it to the ground. On the word "right," pass the weight over the right foot, without any beat. On the word "slide," make a slide to the right with both feet as much as possible at once.

The step in the reverse waltz is the same, except that the turns are to the left instead of to the right.

The lady's step is the same as the gentleman's except that she begins with the contrary foot, and therefore counts "turn, right, slide," "turn, left, slide." And the plan is the same for her step as for the gentleman's, when the words right and left are exchanged one for the other. The numbers designate the time of the music, and the course taken in the figure.

This step is really à deux temps as well as à deux pas. Since in the first half of the step there is no beat at the 2 of the music, but only at the 1, and the 3. And in the second half there is no beat at the 5, but only at the 4, and the 6.

There is another common way of waltzing à deux temps, as follows:

No. 2.—Gentleman's Step In The Figure Of 8, A Deux Temps

Count "left, slide, turn," "right, side, turn." On the word "left," take a step to the left with the left foot. On the word "slide," a slide to the left with both feet as much as possible at once. On the word "turn," turn to the right on the left foot without moving it. On the word "right," take a step to the right with the right foot. On the word "slide," a slide to the right with both feet, as much as possible at once. On the word "turn," turn to the right on the right foot without moving it.

The step in the reverse waltz is the same, except that the turns are to the left instead of to the right.

The lady's step is the same as the gentleman's, except that she begins with the right foot, and therefore counts "right, slide, turn," "left, slide, turn," and the plan is the same for her step as for the gentleman's when the words right and left are exchanged one for the other.

The numbers designate the time of the music, and the course taken in the figure.

This step, like No. 1., is really à deux temps, as well as à deux pas, since the first half of it is completed at the 2 of the music, and the second half at the 5; while at the 3 and 6 of the music, no step or beat of the foot is made, but merely a turn.

Both these steps are used for the galop. But in the galop the halt at each turn is of the same duration as the side step; that is, there are two beats of music for the side step, and two beats of the music for the turn; and if no turn is made, but straight lines continued without turning, as there is no halt, double the number of side steps are made in the same time as would be when turning. In the waltz, the halt at each turn is only of half the duration of the side step; that is, there are two beats of music for the side step, but only one beat for the turn: for this reason, in the waltz you can not go in straight lines sidewise without turning, as you can in the galop, since the alternate steps which should be equal in space, would be unequal in time.

The first half of No. 2, with a halted turn on the right foot, instead of the second half, is taught and used for the German waltz for the gentleman. The lady doing the complete step.

Waltz à Deux Temps (An Amateur, 1843):

The German waltz, à deux temps, is exactly contrary in its principle to the Rhenish waltz. The motion, instead of being always backward or forward, is always directly sideways; and the beats of the feet, instead of being in three time, are in two time.

Gentleman's Step In The Figure Of 8, À Deux Temps

Count "left, slide, turn," "right, side, turn." On the word "left," take a step to the left with the left foot. On the word "slide," a slide to the left with both feet as much as possible at once. On the word "turn," turn to the right on the left foot without moving it. On the word "right," take a step to the right with the right foot. On the word "slide," a slide to the right with both feet, as much as possible at once. On the word "turn," turn to the right on the right foot without moving it. The step in the reverse waltz is the same, except that the turns are to the left instead of to the right. The lady's step is the same as the gentleman's, except that she begins with the right foot, and therefore counts "right, slide, turn," "left, slide, turn," and the plan is the same for her step as for the gentleman's when the words right and left are exchanged one for the other.

The numbers designate the time of the music, and the course taken in the figure.

Gentleman's Step.

This step is really à deux temps, as well as à deux pas, since the first half of it is completed at the 2 of the music, and the second half at the 5; while at the 3 and 6 of the music, no step or beat of the foot is made, but merely a turn.

It is the same as the galop step. But in the galop the halt at each turn is of the same duration as the side step; that is, there are two beats of music for the side step, and two beats of the music for the turn; and if no turn is made, but straight lines continued without turning, as there is no halt, double the number of side steps are made in the same time as would be when turning. In the waltz, the halt at each turn is only of half the duration of the side step; that is, there are two beats of music for the side step, but only one beat for the turn: for this reason, in the waltz you can not go in straight lines sidewise without turning, as you can in the galop, since the alternate steps which should be equal in space, would be unequal in time.

Valse A Deux Tems (Coulon, 1844):

As taught by Mons. E. Coulon.

This waltz came out at the court of Vienna, whence it was brought to us, and has become such a great favourite as to have driven all other waltzes from the field. Unfortunately, as it generally happens in fashionable dances, there are many who launch into them without having taken the trouble of learning the first step. For the benefit of these enterprising waltzers, we shall here lay down the principles by which they may be safely guided.

The Valse à Deux Tems contains three times, like the other waltz; only they are otherwise divided. The first time consists of a sliding step, or glissade; the second is marked by a chassez, which always includes two times in one. A chassez is performed by bringing one leg near the other, then moving it forward, backward, right, left, or round.

The gentleman begins by sliding to the left with his left foot; then performing a chassez towards the left with his right foot, without turning at all during these two times. He then slides backwards with his right leg, turning half round; after which he puts his left leg behind, to perform with it a little chassez forward; turning then half round, for the second time. He must finish with his right foot a little forward, and begin again with his left.

The lady waltzes after the same manner, with the exception, that on the first time she slides to the right with the right foot, and performs the chassez also on the right. She then continues the same as the gentleman, but à contre jambe, that is, she slides with her right foot, backwards, when the gentleman slides with his left foot to the left; and when the gentleman slides with his right foot, backwards, she slides with her left foot to the left.

One of the first principles of this waltz is never to jump, but only to slide. The steps must be made rather wide, and the knees kept slightly bent.

Several gentleman, who may be designated as les étoiles de la Valse, have danced the Valse à Deux Tems, à rebours (or contrariwise); the effect is very pretty, though, at the same time, its execution is difficult. The principles are the same as already described, but danced à contre pied, that is to say, the left foot is slid backwards during the first time, and the right sideways, during the second time.

We shall conclude our remarks by recommending the Valse à Deux Tems by Jullien,—the prettiest we have heard, and certainly the best calculated to bring the rhythm to the understanding of beginners.

Valse À Deux Tems (Saunders, 1845):

The Valse à Deux Tems is formed like other Waltzes of three times, but these times are differently divided. The first step is a glissade, the second a slightly-marked chassez.

The gentleman commences by sliding his left foot to the left, and then does a chassez towards the left with his right foot. During this step there is no turn made.

The right foot is then made to slide back whilst turning half; a small chassez is then performed with the left foot, and the right foot is brought a little forward as the circle is completed.

The lady commences with the right foot and performs the chassez with the right. The lady then does the same as the gentleman à contre jambe; or in other words, the lady slides the right foot back when the gentleman slides to the left; and when the gentleman slides his right foot back, the lady slides her left foot to the left.

In this Waltz there must be no jump: all must be smooth and even—the steps being only glissades and chassezs.

To dance "La Polka" and the "Valse à Deux Tems" with elegance, it is quite necessary to receive instructions of a professor; for though a Ball Room Guide may keep the dances in the memory of those who have studied, yet it can never throughly instruct, unaided by a master.

The Waltze A Deux Temps (Cellarius, 1847, Fashionable Dancing):

The waltze a deux temps is, perhaps, justly called the waltze of the day, and does not seem destined soon to lose the unanimous favour in which it is held both in France and other countries. The opinion, long accredited, that it is in opposition to the time, could not, as I have already noticed, bear the test of reason nor even of the ear. It was pretended too, that it sinned on the side of grace, and that the old waltze was more calculated to show off the dancers, and particularly the ladies, while the new one presented to the eye only a short abrupt course, without any of those balancings of the body and undulations of the head, which were an indispensable ornament of the real waltze.

It is very difficult, I think, to come to any precise agreement as to the word, taste, which often varies with the times, and has like so many things of this world its vicissitudes and conventionalities. Every people, every age, imagines that the most graceful dance in the world is beyond contradiction its own. We may give excellent reasons in favour of the waltze a trois temps; and I do not doubt that a century ago, they gave just as good in behalf of the saraband, the coranto, and the minuet. At all times the dances in fashion found natural enemies in those they had just dethroned.

I think before considering whether a dance or a waltze is, or is not, calculated to please the spectators, we should enquire if it is likely to please the dancers; that we shall find, is the essential point. Now I appeal to the waltzers themselves;-do they experience the same pleasure in making one uniform circle about a room, upon an equal movement, as when they spring with that fascinating vivacity, which the waltze a deux temps alone permits, relaxing or quickening their pace at will, promenading their partner in every way, now obliging her to fall back, now themselves retreating, going to the right, to the left, varying their pace almost at every step, and arriving at that sort of giddiness, which I may venture to call intoxication, without fear of contradiction from the real lovers of the waltze?

It is not for me in this place to defend, and still less to puff, the waltze a deux temps, but I may venture to observe, that I have never heard it condemned except by those who have never danced it. Its greatest enemies, the moment they have themselves been able to appreciate its advantages,have immediately enlisted amongst its most zealous partizans.

The music of this waltze is in the same time as that of the waltze a trois temps* except that the orchestra should rather quicken the movement and mark it with particular care.

*M.M. [dotted half note] = 88 [meaning 264 quarter notes per minute]

The step is very simple, being nothing more than the gallop executed by either leg while turning; but instead of springing, it is essential to glissade thoroughly, avoiding every thing like starts or jerks.

I have already explained the position of the foot in my notice of the waltze a trois temps. The dancer should keep his knee slightly bent; if they are too tense, they naturally occasion stiffness, and force the waltzer to spring; but this bending should be very little marked, and almost imperceptible to the eye; too great a curving of the hams not only produces an ungraceful effect to the spectator, but is quite as injurious to the waltze as too much stiffness.

It is requisite to make a step to every beat-that is, to glissade with one foot, and to chasser with the other. Differing in this from the waltze a trois temps, which describes a circle, the waltze a deux temps is danced squarely, and turns only upon the glissade. It is essential to note this difference of movement in order to appreciate the character of the two dances.

The position also of the gentleman is not the same in the waltze a deux temps as in that a trois. He must not face his partner, but be a little to her right, slightly inclining his right shoulder, which allows him to spring well when carrying along the lady.

I have already expressed my regret that custom should have given to this dance the name of waltze a deux temps, instead of a deux pas. The term three steps (pas) would have avoided much confusion by indicating that two steps were to be executed to three beats of the music; the first step to the first beat-the second beat to be passed over-and the second step to the third beat. By these means one is always sure of keeping time.

The gentleman in the waltze a deux temps sets out with the left foot, and the lady with the right.

What I have said in regard to the attitude of the gentleman, applies in part to the lady. She should equally avoid stiffness of the legs as well as of the arm, which is joined to that of her partner, and abstain from leaning heavily upon the hand or shoulder, which in waltze-language is termed clinging.

The defect of most French dancers, who have not as yet familiarized themselves with the waltze a deux temps is, that they throw themselves too much back, turn aside their head, and hollow their waist, all of which contributes to make them heavy on one side, and is opposed to the oblique intention of the waltze.

The German ladies do not hesitate to lean slightly forward on the gentleman, which greatly facilitates the execution of many movements imposed upon them. However light and slender a lady may be, she will not be light upon the arm of her partner, if she at all detaches herself from him by any motion of the body.

There is then, we perceive, very little complication in the principles of the waltze a deux temps. The step is very simple, and easily acquired in a single lesson; the attitude is no other than what is pointed out by nature. But notwithstanding its apparent simplicity, this waltze presents real difficulties, if we at all desire to attain a certain degree of perfection,-difficulties that are to be conquered only by much practice, and which depend upon details of sufficient importance for me to think it requisite to devote a particular chapter to them. I make no pretensions, in this place, as I have already observed, to explain the mechanism, but only the character, and, if I may so say, the style, of this waltze, which less than any other will endure a mediocre execution.

IX. Advice to the Waltzers a Deux Temps

During the many years that I have devoted myself to the tuition of dancing, there has seldom passed a day, in which I have not had many waltzers under my eyes. It is rarely that each new pupil does not by his defects, his habits, and his less or greater progress, suggest some profitable hint for the theory, or practice of the art-an art so simple in appearance, and yet so complicated by so many shades and details, if we wish to fathom it thoroughly.

Under the title of Advice to Waltzers , I have brought together in this chapter such of my observations as I consider the most essential, and even as forming the necessary whole for the education of a waltzer a deux temps.

The conducting of the lady is not the most easy nor the least delicate part of the waltzer's duty. A thousand rocks present themselves to him the moment he finds himself flung into the whirl of the ball. If he at all jostles the other dancers, if he can not keep clear of the most inexperienced, even of the couples a trois temps, which are so great an impediment to those a deux temps-if he is not sufficiently sure of the music to keep time when the orchestra quickens or slackens it, or even when his partner loses it-then he can not be considered as a skilful waltzer. This habit, or, I may call it, manoeuvre of the waltze, is not acquired without much practice, and the dancing academy has, in this respect, it must be owned, advantages that nothing can replace. It allows the novice to familiarize himself with the crowd, offering him as it were a preliminary glance at the tumult of a ball-room. He is thus able to learn beforehand how to find out his position, and not to serve in the midst of the drawing-room an apprenticeship which is always dangerous, and particularly on first appearance.

To waltze well, it is not enough to guide the lady always in the same vein, which would speedily bring back the uniformity of the old waltze; it is requisite to know how at one time to cause her to retrograde, making the waltze step not more obliquely but in a straight line, and at another to oblige her to advance upon himself by making the same step backwards. Some waltzers even make the redowa aside, which is not without grace when executed in harmony with the lady, and when the step can be regained by the other foot without losing the time.

If there is sufficient space, the dancer should extend his step, and take that impetuous course, that the Germans execute so well and which is one of the happiest characteristics of this waltze. If the space is narrow, it is necessary to stop short and to confine the step so as only to form a circle.

To know how to shade and blend the dance, is one of the great merits of the waltzer.

I have seen consummate waltzers spring off with the rapidity of lightning, at once so quick and so light that one might have thought they were going to fly from earth with their partners, and then suddenly break off and fall into a pace so slow and gentle that their movements could scarcely be perceived.

This is the place to say a few words upon the waltze called a l'envers, which belongs to the waltze a deux temps, and even represents one of the most original trait, in its aspect already so varied.

The gentleman instead of springing to the left, as I have said a little above, may if he pleases start off on the right, and continue drawing his partner after in the same direction. This is termed the waltze a l'envers. As may be easily seen, it is only the usual step taken in an opposite direction, and this evolution is executed also in the polka. But it must be admitted that the l'envers offers more difficulty in the waltze a deux temps, of which the step is more hurried, and regulated by a rhythm more rapid.

Heaven forbid that I should proscribe the waltze a l'envers, which is not only agreeable as a change, but becomes in certain cases even necessary, when it is required to avoid a couple presenting themselves unexpectedly; I think however, it should be used with a certain degree of caution, and that care should be taken not to engage in it before the time.

A dancer, who is not quite sure of himself would do wrong to undertake this movement prematurely, for fear of acquiring bad habits, for it should be remembered that to waltze a l'envers , is not the natural mode, and always requires a little effort. If, however we wish to describe the whole round of a ball-room, there will be a moment when it is necessary to waltze not only a l'envers, but also a rebours (backward) which is quite another sort of difficulty.

The sort of pivoting, which must be used to catch the precise moment of the rebours , constrains the waltzer, who has not acquired all the skill and ease required for springing, makes him lose the step, sometimes even his equilibrium, and in any case compels the employment of a force upon his partner, which the rules of the real waltze can never allow. I would not recommend even experienced dancers to indulge too much in the waltze a l'envers; it should always be the accessary only, and not the principal. I have seen in my own course, dancers, who had attained a certain proficiency, yet in part lose their advantages by persisting in waltzing too much a l'envers, and become stiff, constrained, their steps unnatural, while they had no longer the power of pacing freely with the natural impulse of the waltze; and all this from a fancy for devoting themselves exclusively to a certain exercise, which when abused is nothing more than a peculiar trick of strength.

We should abstain entirely from this habit in crowded ball-rooms where we have only a confined space before us. A waltzer a l'envers in general directs himself with less facility than one a l'endroit . To jostle, or be jostled, in a ball-room, is always, if not a grave fault, at least one of those unlucky accidents, that can not be too carefully avoided.

Now if it be true that it is only with extreme labour we are able to manoeuvre in a confined circle of waltzers, what is the use of creating imaginary difficulties, and meet a danger, out of which there are so few chances of escaping with credit.

X. Sequel to the Advice to Waltzes a Deux Temps

I have spoken of the step of the waltze a deux temps, of the different modes it allows, of the conduct of the lady, of every thing that can be considered as an elementary part of it; I have now to advise waltzers to attend with the utmost care to their carriage, a point no less essential than all the rest, and which the master can not neglect without the greatest injury to his pupils. It is in vain, I should say to the dancers, that you can execute the step with facility-in vain that you can perform the most difficult evolutions; if at the same time your neck is not at a distance from the shoulders, if your arm is distorted, your back bent, and your legs stiff, you need never aspire to the title of good waltzers.

It was believed for a time, and above all at the epoch when the waltze a deux temps came first into fashion, that it required a peculiar sort of affectation in the carriage. Many imagined that no one could be cited as a fashionable waltzer without some sort of mannerism, either in fully extending the arm to the lady at the risk of blinding the nearest couple, or in rounding the elbow like a handle, or in flinging back the head in a sort of frenzy, or, in a word, by affecting some singularity of attitude. Good taste, however, has done good justice to all these affectations, which did real injury to the waltze, which was for a long time considered to be mad, or eccentric, while nothing in the world can be more easy or natural. As for me, I never cease recommending to my pupils simplicity and nature in their waltzing; I do not even allow that the lady's wrist should be kept elevated, the fingers hanging without those of the gentlemen, according to the mode that some have attempted to establish. The best way is to hold the lady quite simply by the hand, and to conduct her with as little effort as if leading her in a promenade. The drawing-room waltze should be never considered as a forced exercise, and still less as an affair of parade; nor can we too closely approach to that graceful ease which people of fashion evince in all their actions. Whoever in waltzing perverts his usual habits, or takes a manner, an attitude, or even a look of command, may reckon before-hand that he waltzes with pretension,-that is to say, badly. Nevertheless while offering my advice to the gentlemen, I cannot forbear addressing myself at the same time to the ladies, who should also take to themselves whatever I have said in relation to ease of movement and simplicity of attitude. It would be doubtless superfluous to insist with them on the necessity of maintaining a graceful and natural attitude.

I have already, when speaking of the polka, recommended the ladies to allow themselves to be directed by their partner, to trust entirely to him without in any case endeavouring to follow their own impulses; and this advice is particularly applicable to the waltze a deux temps. The lady, who in the middle of the ball, should herself seek to avoid the other couples, would run the risk of thwarting the plans of her partner, who alone can assure her safety in the midst of people crossing and jostling in every direction. In the same way when the lady desires to rest, she should warn her partner and not stop mid-way of herself. It is to him only belongs the choice of a place where he may place her in safety.

The gentleman should be careful not to let go of his partner 'till he perceives she is completely still. The rotatory motion, even after the stop, is often so vivid, that he would risk seeing her lose her equilibrium, if he detached himself in the midst of a round.

In speaking of the ladies' waltzing, may I be permitted to hazard a counsel, and which besides is the opinion of the greater part of my pupils. Good waltzers are scarce now-a-days amongst the gentlemen, but it must also be observed, at the risk of being charged with want of gallantry, that their number is equally limited among the ladies. One may well be surprised at this, considering all those natural qualities of grace and lightness, which make the generality of dances so easy to them.

It has been too generally imagined that the study of the waltze is almost unnecessary for the ladies, that their part consisting only in suffering themselves to be directed, they have only to follow the impulse given to them without any need of preliminary knowledge. Beyond doubt the gentleman's part is the most arduous, and to all appearance has more of care and detail, since he must do at the same time himself and for his partner; but to affirm that the lady's part is altogether negative, and not to perceive that she also has much art and a peculiar skill to acquire, is an error against which I cannot too strongly protest. A bad waltzer is certainly a real scourge for the ladies, and it may be easily conceived that they seek to guard against it; but it must also be allowed that a bad valseuse-and we cannot deny that they too may be found-is scarcely a less inconvenience. Not only does her want of skill injure herself, but it wears, and even paralyzes her partner, who with all his skill cannot supply her total want of practice. A gentleman, who finds he has to direct a lady altogether inexperienced, is reduced to the lamentable necessity of employing force, which infallibly destroys all harmony and all grace; he no longer waltzes; he raises, he supports, he drags along.

Ladies, who imagine that a few essays made in private, and under the too indulged auspices of friends and parents, will enable them to appear with success before the world, too often deceive themselves; and when I say that the counsels of a master are always useful, if not absolutely indispensable, I hope I shall not be accused of thinking in a narrow professional spirit when I have nothing in view but the delights and advance of the art of waltzing.

It is a master only, who by virtue of his office may venture to point out to a lady the real execution of the step, and the attitude she should maintain. Is it in the midst of a ball, when the gentleman is on the point of starting, that he can take upon himself to tell the lady that her step is imperfect, her hand badly placed, that she leans heavily on her partner, and throws herself too much backward, and so many other details, which, from want of being pointed out at first, engender defect that may be considered as irremediable? In fact, a gentleman may scrupulously correct himself, he may hear the truth from his friends, but a lady is much more frequently flattered than admonished. It is a master only who will undertake the painful, but necessary, task of censure, or at least, he will point out those indispensable principles, which are the fruit of observation, and which all the intelligence in the world is unable to supply. For the rest, and without seeking in any wise to palliate the extreme rigour of my advice, I ought to add, that the few lessons, which seem to me requisite for the valseuse, have nothing very alarming in them. Their education is much more quickly accomplished than that of the waltzer. I have seen the greater part of the ladies, who have trusted themselves to my tuition, in a state to figure at a ball after a very few lessons, especially if they have had to do with a skilful partner. In fact, we may easily conceive that much less is necessary to be done for the carriage of the ladies, who are naturally graceful and elegant; it is only the first indications that are required to be inculcated on them; their peculiar aptitude for every kind of dance soon outstrips the lessons of the master.

I cannot terminate these general remarks-which might be infinitely extended, so many are the shades and details in the teaching and practice of the waltze a deux temps -without reminding the professors that in regulating the step and attitudes of their pupils they should endeavour to preserve the characteristics of each, and should take care that while the waltzers appear elegant and fashionable in their movements, they still remain themselves.

I have remarked-and no doubt others have done the same-that there are almost as many sorts of waltzers, as there are kinds of dances. One is distinguished by his impetuosity, his fire; his attitude without being exactly disordered has not all the prescribed regularity; but he makes amends for these defects by the inappreciable qualities of warmth and vigour. Another waltzes calmly and without the least agitation; if he does not carry away his partner, in requital he impresses upon her a motion calm and sweet, that may be compared to a rocking, and which although a merit opposite to the dancer of fire and spirit, does not the less constitute one of the qualities of a good dancer.

It sometimes happens that without exactly springing, certain waltzers seem at every step to slightly leave the ground by means of a kind of continued rising, which is not without grace, and above all facilitates the execution of the valse course.

The master must be careful not to attempt reforming any of those peculiarities which are often the result in each individual of constitution and nature. Fortunately one may be an equally good waltzer with the most opposite qualities, and the questions of self-love and rivalry amongst them reduce themselves to nothing.

That such a waltzer is preferred to such an one in the world is not at all surprising; it often happens not because the one is superior to the other, but simply because his step is more in harmony with that of such or such a lady. The varieties that exist amongst the waltzers reproduce themselves amongst the valseuses.

These dissimilitudes or affections constitute one of the great charms of the waltze a deux temps. The expert dancer has the prospect of finding a new waltze almost at every fresh invitation. Uniformity exists only for novices or the unskilful.

Valse A Deux Tems (Hazard, 1849):

[Nearly verbatim copy of Coulon 1844]

This waltz came out at the court of Vienna, whence it was brought to us, and has become such a great favourite.

The Valse à Deux Tems contains three measures, like the other waltz; only they are otherwise divided. The first time consists of a sliding step, or glissade; the second is marked by a chassez, which always includes two times in one. A chassez is performed by bringing one leg near the other, then moving it forward, backward, right, left, or round.

The gentleman begins by sliding to the left with his left foot; then performing a chassez towards the left with his right foot, without turning at all during these two times. He then slides backwards with his right leg, turning half round; after which he puts his left leg behind, to perform with it a little chassez forward; turning then half round, for the second time. He must finish with his right foot a little forward, and begin again with his left.

The lady waltzes after the same manner, with the exception, that on the first time she slides to the right with the right foot, and performs the chassez also on the right. She then continues the same as the gentleman, but à contre jambe, that is, she slides with her right foot, backwards, when the gentleman slides with his left foot to the left; and when the gentleman slides with his right foot, backwards, she slides with her left foot to the left.

One of the first principles of this waltz is never to jump, but only to slide. The steps must be made rather wide, and the knees kept slightly bent.

This waltz admits of two movements—a quick and a slow one. The slow one requires four measures in the the round. The quick one only two. The former is by far the more graceful of the two, and has over the latter the advantage of requiring less motion. It is particularly suitable to persons of a tall stature.

Valse A Deux Tems (Kent & Co., 1850):

The Gentleman slides to the left with left foot and chassez towards the left with right foot, without turning. He next slides backwards with right leg, turning half round; then moves the left leg behind using the little chassez forward, turning half round for the second time.

The Lady uses the foot a contre to the Gentleman throughout the figure.

Deux Temps (Hillgrove, 1857):

Music in Two-Four Time.

The Deux Temps contains "three times," only they are otherwise divided and accented—two of the times being included in one, or rather one of the times divided in two. The first step consists of a glissade or slide; the second is a chassez, including two times in one. (A chassez is performed by bringing one foot near to the other, which is then moved forward, backward, right, left or round.)

The position for this dance is the same as for the polka or waltz, (see description, page 79). The dance is very simple, and may be easily acquired in a single lesson, as it is precisely the same as that of the gallop.

1st. The gentleman begins by sliding to the left with his left foot, then performing a chassez towards the left with his right foot, without turning at all during the first two times.

2d. He then slides his right foot backwards turning half round, after which he places his left foot behind to perform with it a chassez forward, again turning half round at the same time. He must finish with his right foot forward, and begin again with his left foot as before.

To dance the Deux Temps well, it must be danced with short steps, the feet sliding so smoothly over the surface of the floor that they scarcely ever seem to be raised above it. Anything like jumping is altogether inadmissible; moreover, though a very quick dance, it must be danced very quietly and elegantly, and every inclination to romping or other vulgar movements must be carefully checked and corrected. This is the besetting sin of dancing; a sin, however, which is committed by bad dancers only, because it is easier to do anything wrong than to do it right or well.

A gentleman should practise this dance long in private before he attempts it in public, for he looks exceedingly vulgar and clownish if not quite au fait, and he subjects his partner to all sorts of inconveniences, not to speak of the kicks and bruises. Many bold, foolish, or conceited young men, misled by the apparent easiness of the step, undertake to lead a lady through the Deux Temps after one or two private lessons, and perhaps to their own great satisfaction, they do get through it. But little are they aware of the discomfort, perhaps pain, which they occasion; and if they only saw themselves in a glass (what they look like), they would blush at the inferior position which they occupy in a gay and graceful assembly.

The Deux Temps should not be danced long without stopping, for after a few turns it becomes laborious, and where labor is very apparent, grace is wanting.

The Valse A Deux Temps (Bland, 1868):

[Abbreviated copy of Coulon 1844]

The Valse à Deux Tems contains three times, the first consists of a glissade; the second of a chassez, which includes two times in one.

The Gentleman begins by sliding to the left with his left foot, he then performs a chassez towards the left with his right foot, without turning at all during these two times; he then slides backwards with his right leg, turning half round, after which he puts his left foot behind, to perform with it a little chassez forward; turning half round for the second time, he must finish with his right foot a little forward, and begin again with his left.

The Lady waltzes after the same manner, with the exception, that, on the first time she slides to the right with the right foot, and performs the chassez also to the right. She then continues the same as the gentleman, but à contre pied, that is, she slides with her right backwards when the gentleman slides with his left foot to the left, and when the gentleman slides with his right foot backwards, she slides with her left foot to the left.

One of the first principles of this waltz is, never to jump, but only to slide, and the knees kept slightly bent.

The Valse A Deux Temps (Routledge, 1868):

We are indebted to the mirth-loving capital of Austria for this brilliant Valse, which was, as we have observed elsewhere, introduced to our notice shortly before the Polka appeared in England, and owed its popularity to the revolution in public taste effected by that dance.

Although the Polka has gone out of fashion, the Valse à Deux Temps still reigns supreme; but within the last two years a dangerous rival has arisen, which may perhaps drive it in its turn from the prominent position which, for more than twenty seasons, it has maintained. This rival is the New Valse, of which we shall speak in its place; but we must now describe the step of the Valse à Deux Temps.

We have already remarked that this Valse is incorrect in time. Two steps can never properly be made to occupy the space of three beats in the music. The ear requires that each beat shall have its step; unless, as in the Cellarius, an express pause be made on one beat. This inaccuracy in the measure has exposed the Valse à Deux Temps to the just censure of musicians, but has never interfered with its success among dancers. We must caution our readers, however, against one mistake often made by the inexperienced. They imagine that it is unnecessary to observe any rule of time in this dance, and are perfectly careless whether they begin the step at the beginning, end, or middle of the bar. This is quite inadmissible. Every bar must contain within its three beats two steps. These steps must begin and end strictly with the beginning and end of each bar; otherwise a hopeless confusion of the measure will ensue. Precision in this matter is the more requisite, because of the peculiarity in the measure. If the first step in each bar be not strongly marked, the valse measure has no chance of making itself apparent; and the dance becomes a meaningless galop.

The step contains two movements, a glissade and a chassez, following each other quickly in the same direction. Gentleman begins as usual with his left foot; lady with her right.

1st beat.— Glissade to the left with left foot.

2nd and 3rd beats.—Chassez in the same direction with right foot; do not turn in this first bar.

2nd bar, 1st beat.—Slide right foot backwards, turning half round.

2nd and 3rd beat.—Pass left foot behind right, and chassez forward with it, turning half round to complete the figure en tournant. Finish with right foot in front, and begin over again with left foot.

There is no variation in this step; but you can vary the movement by going backwards or forwards at pleasure, instead of continuing the rotatory motion. The Valse à Deux Temps, like the Polka, admits of a reverse step; but it is difficult, and looks awkward unless executed to perfection. The first requisite in this Valse is to avoid all jumping movements. The feet must glide smoothly and swiftly over the floor, and be raised from it as little as possible. Being so very quick a dance, it must be performed quietly, otherwise it is liable to become ungraceful and vulgar. The steps should be short, and the knees slightly bent.

As the movement is necessarily very rapid, the danger of collisions is proportionately increased; and gentlemen will do well to remember and act upon the cautions contained in the earlier pages of this little work, under the head of "The Polka."

They should also be scrupulous not to attempt to conduct a lady through this Valse until they have thoroughly mastered the step and well practised the figure en tournant. Awkwardness or inexperience doubles the risks of a collision; which, in this extremely rapid dance, might be attended with serious consequences.

The Deux Temps is a somewhat fatiguing valse, and after two or three turns round the room, the gentleman should pause to allow his partner to rest. He should be careful to select a lady whose height does not present too striking a contrast to his own; for it looks ridiculous to see a tall man dancing with a short woman, or vice versa. This observation applies to all round dances, but especially to the valse, in any of its forms.

Deux Temps (Spencer, 1869):

The Valse A Deux Temps is very popular, and does not appear likely for some time to lose its favor. The music is rhythmed, the same as that of the Trois Temps, except that it should be played quicker and accentuated with especial care.

The step is very simple, being similar to that of the Galop, but must be carefully glided, avoiding leaps and jerks.

The lady should avoid leaning heavily on the shoulder or arm of her partner. The greatest defect with most ladies who are not accustomed to the Valse A Deux Temps, is to throw themselves back, to turn away the head, and to warp the figure, which gives an awkward heaviness to their appearance, and it out of character with the spirit of the dance. Ladies should bend slightly forward to their partners, as it will greatly facilitate the execution of the various movements they may be required to make.

The effect of the rotary motion, even after stopping, is sometimes so great that a gentleman would risk his partner losing her equilibrium by detaching himself from her too suddenly; he should therefore take care never to relinquish his lady until he feels that she has entirely recovered herself.

The management of his partner is not the most easy, nor is it the least delicate part of the waltzer's task, and a lady who waltzes badly not only loses much of her charms, but she constrains or paralyzes even her partner, who, whatever may be his skill, cannot make up for her defects. Being compelled to direct an inexperienced waltzer, he is reduced to the painful extremity of using an amount of force which infallibly destroys all harmony and grace; he no longer waltzes, but supports, bears or drags his partner along with him.

A gentleman may correct his faults; he may hear truth from the lips of his friends; but a lady is more accustomed to adulation that to criticism. A master only can, by virtue of his delegated authority, point out to a lady the steps and attitudes she should endeavor to acquire. He only will impose upon himself the necessary duty of directing her attention to those indispensable principles, which are the fruits of observation and experience.

The Deux Temps (Cartier & Baron, 1879):

[Likely an opaque description of the Cellarius Deux Temps]

The steps of the Deux Temps is similar to that of the galop, the difference being in its accentuation, and danced to waltz music (3-4 time). The steps of the Deux Temps are counted on the first and third beat of the bar, a pause being made on second beat; thus—one and two.

The Galop (La Valse a Deux Temps) (Gilbert, 1890):

M. M. = 144

1. Glissé.

2. Chassé

Galop Sidewise.

Slide left foot to side (2d), 1; draw right to left and immediately slide left to side (chassé), & 2; one measure. Repeat, commending with the right foot.

Counterpart for lady.

[...]

The method of practicing the turn, guiding, and le changement de tour in the Polka, may be applied in this dance.

La Valse a Deux Temps (Gilbert, 1890):

[Likely an opaque description of the Cellarius Deux Temps]

For description of movements see the Galop [1. Glissé, 2. Chassé]. When applied to the Waltz, the movements are made on the first and third counts in the measure.

Valse En Deux Temps (de Soria Fils, 1895):

La Valse En Deux Temps est, croit-on, d'origine russe. Elle se danse sur une mesure en trois temps, et, pour être bien dansée, il lui faut un mouvement vif.

[La Valse En Deux Temps is believed to be of Russian origin. She dances on a measure of three (temps?), and to be danced well, requires quick movement.]

Tous les temps doivent être glissés.

[All movements must be gliding.]

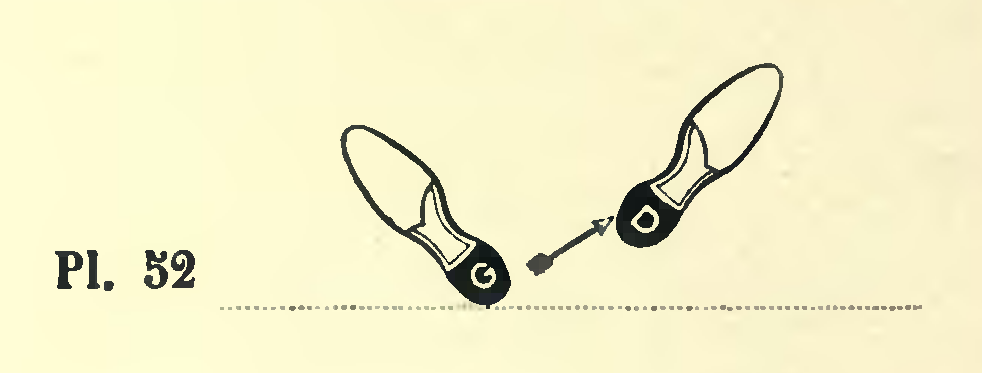

1er temps — Glisser le pied droit en avant et vers la droite, Pl. 52.

[Slide the right foot forward and to the right, as below.]

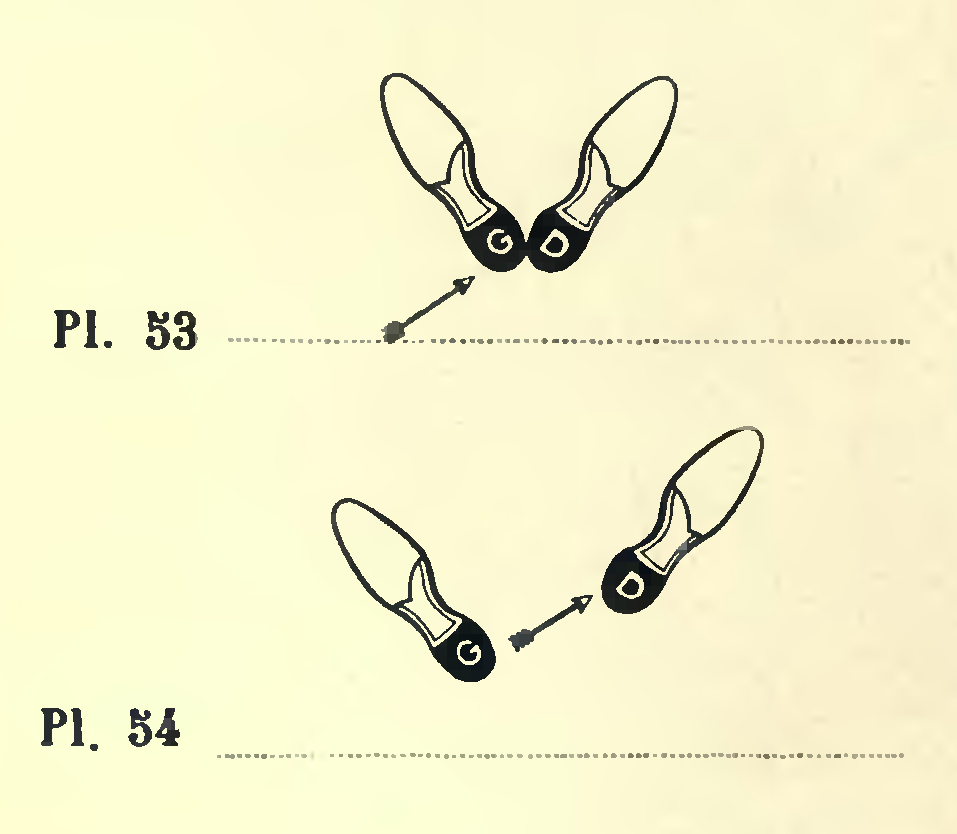

2me temps — (Sur les 2me et 3me temps de la musique).

[Second movement, on the second and third counts of the music.]

Le pied gauche chasse vivement le pied droit en avant, Pl. 53 et 54.

[The left foot briskly chases the right foot in front.]

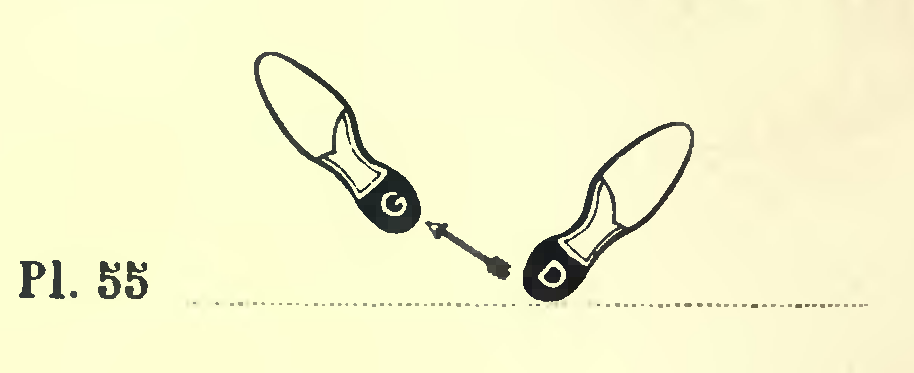

Pour la deuxième mesure, faire de même du pied gauche, Pl. 55.

[For the second measure, do the same with the left foot.]

The Valse À Deux Temps (Ledgett-Byrne, 1899):

The Valse à Deux Temps is peculiar, in its being practically incorrect to time, the music of all Valses being composed in 3-4 time, and, the steps of above being but two, it follows that one time of beat in the bar must be filled up, which is done in this case by a pause.

Many who attempt this dance no appear to imagine they can disregard the time altogether, but the importance of attention to this point is so apparent in some cases as to render the dancing of even aged and somewhat infirm persons more presentable than that of youth and agility when deficient in this qualification.

For Gentleman.

Slide left foot to the left (slightly bending knee to give elasticity while carefully keeping body upright), bring right foot up to the left, and slide again forward with the left foot ... 1 bar.

Slide right foot back, followed by left to the back of right, when slide right foot to the front; in doing this make a half turn. Lady commences with the right foot.

The Deux-Temps (Two Step) (Wilson, 1899):

Slide with the right foot straight to the side, bring the hollow of the left foot to the heel of the right and change weight to left foot (1). The slide is accented, and as little time as possible given to the change.

Step forward on the right foot (2), and bring left foot forward so that the toes are opposite the hollow of the right foot, and at the same time pivot to the right on the right foot.

Slide with the left foot to the side, bring the hollow of the right foot to the heel of the left and change weight to right foot (1).

Step backward on left foot and bring right foot to position with toe opposite the hollow of the left foot, pivoting, at the same time, to the right, on the left foot. Then recommence with the right foot.

The Reverse is accomplished by stepping forward with the left foot and backward with the right on 2, and pivoting to the left instead of to the right.